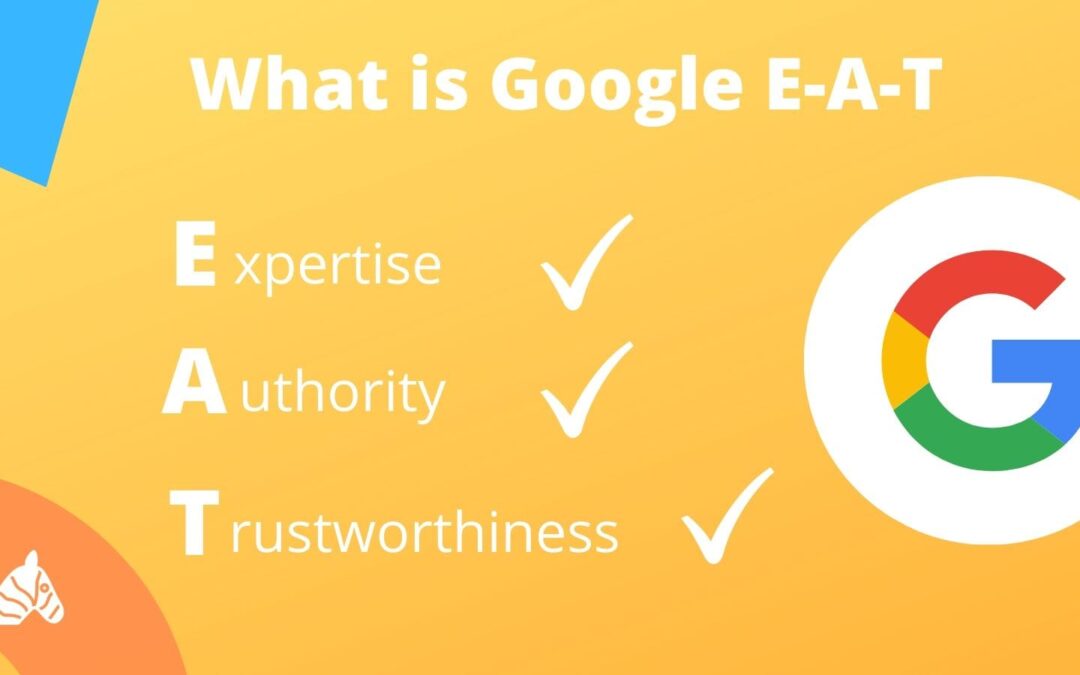

E‑A-T- stands for expertise, authoritativeness, and trustworthiness. It comes from Google’s Search Quality Rater Guidelines—a 168-page document used by human quality raters to assess the quality of Google’s search results.

Google published this document online in 2013 to “help webmasters understand what Google looks for in a web page.”

E‑A-T is important for all queries, but some more so than others.

If you’re just searching for pictures of cute cats, then E‑A-T probably doesn’t matter that much. The topic is subjective, and it’s no big deal if you see a cat you don’t think is cute.

If you’re searching for the correct dosage of aspirin when pregnant, on the other hand, then E‑A-T is undoubtedly important. If Google were to surface content on this topic written by a clueless writer, published on an untrustworthy website that lacks authority, then the probability of that content being inaccurate or misleading is high.

Given the nature of the information being sought here, that’s not just mildly inconvenient—it’s potentially life-threatening.

E‑A-T is also important for queries like “how to improve credit score.” Here, advice from the clueless and unauthoritative is unlikely to be legit and shouldn’t be trusted.

Google refers to these kinds of topics as YMYL (Your Money or Your Life) topics:

Some types of pages or topics could potentially impact a person’s future happiness, health, financial stability, or safety.

We call such pages “Your Money or Your Life” pages, or YMYL.

If your site is built around a YMYL topic, then demonstrating EAT is crucial.

Expertise, authoritativeness, and trustworthiness are similar concepts—but not identical. So, they’re each evaluated independently using a different set of criteria.

Expertise

Expertise means to have a high level of knowledge or skill in a particular field. It’s evaluated primarily at the content-level, not at the website or organizational level. Google is looking for content created by a subject matter expert.

For YMYL topics, this is about the formal expertise, qualifications, and education of the content creator. For example, a chartered accountant is more qualified to write about tax preparation than someone who’s read a few posts at r/personalfinance.

Formal expertise is important for YMYL topics such as medical, financial, or legal advice.

For non-YMYL topics, it’s about demonstrating relevant life experience and “everyday expertise.”

Some topics require less formal expertise. […] If it seems as if the person creating the content has the type and amount of life experience to make him or her an “expert” on the topic, we will value this “everyday expertise” and not penalize the person/webpage/website for not having “formal” education or training in the field.

Google also says that “everyday expertise” is enough for some YMYL topics. For example, take a query like “what does it feel like to have cancer.” Someone living with the disease is better placed to answer this than a qualified doctor with years of experience.

It’s even possible to have everyday expertise in YMYL topics. For example, there are forums and support pages for people with specific diseases. Sharing personal experience is a form of everyday expertise.

Authoritativeness

Authority is about reputation, particularly among other experts and influencers in the industry. Quite simply, when others see an individual or website as the go-to source of information about a topic, that’s authority.

To evaluate authority, raters search the web for insights into the reputation of the website or individual.

Use reputation research to find out what real users, as well as experts, think about a website. Look for reviews, references, recommendations by experts, news articles, and other credible information created/written by individuals about the website.

Raters are told to look for independent sources when doing this.

When searching for reputation information, try to find sources that were not written or created by the website, the company itself, or the individual.

Wikipedia is one good source of information that Google mentions.

Wikipedia articles can help you learn about a company and may include information specific to reputation, such as awards and other forms of recognition, or also controversies and issues.

It’s important to remember that authority is a relative concept. While Elon Musk and Tesla are authoritative sources of information about electric vehicles, they have little to no authority when it comes to SEO.

It’s also the case that some people and websites are uniquely authoritative when it comes to certain topics. For example, the most authoritative source of lyrics to Coldplay songs is their official website. And the most authoritative source of information for beef grades in the US is the USDA.

Trustworthiness

Trust is about the legitimacy, transparency, and accuracy of the website and its content.

Raters look for a number of things to evaluate trustworthiness, including whether the website states who is responsible for published content. This is particularly important for YMYL queries, but applies to non-YMYL queries too.

YMYL websites demand a high degree of trust, so they generally need satisfying information about who is responsible for the content of the site.

Having sufficient contact information is also important, especially for YMYL topics and online stores.

If a store or financial transaction website has just an email address and physical address, it may be difficult to get help if there are issues with the transaction. Likewise, many other types of YMYL websites also require a high degree of user trust.

Raters also take into account content accuracy.

For news articles and information pages, high quality MC must be factually accurate for the topic and must be supported by expert consensus where such consensus exists.

Citing trustworthy sources is part of this.

[an article] with a satisfying amount of accurate information and trustworthy external references can usually be rated in the High range.

Just remember that trust, like authoritativeness, is a relative concept. People and websites can’t be perceived as trustworthy in all areas. We’re a trustworthy source of information about SEO, but not bodybuilding.

Kind of, at least according to Google’s Public Liaison of Search, Danny Sullivan:

Confused? Let me explain.

You see, for something to be a “ranking factor,” it has to be something tangible that a computer can understand and evaluate.

Perhaps the most obvious example of this is the number of backlinks to a page.

Google crawls the web far and wide so they know how many backlinks point to most pages. They can easily create a computer program that ranks pages with the most high-quality backlinks.

The problem with expertise, authoritativeness, and trust is that—while they’re desirable qualities of content—they’re fundamentally human concepts. You can’t tell a computer to rank pages with E‑A-T higher because it only understands bits and bytes.

Here’s Google’s solution to this problem:

First, their search engineers think of algorithm tweaks that might improve search result quality.

Second, they show search results to Quality Raters with and without the proposed change implemented. Their job is to provide feedback to Google, and they aren’t told which set of results is which.

Third, Google uses the feedback to decide whether the proposed tweak had a positive or negative impact on search results. If the results are positive, the change is implemented.

Using this process, Google engineers are able to understand the tangible signals that align with E‑A-T and adjust the ranking algorithms accordingly.

Ben Gomes, Google’s Vice President of Search, offered a fantastic tldr; version of everything above in an interview with CNBC in 2018:

You can view the rater guidelines as where we want the search algorithm to go. They don’t tell you how the algorithm is ranking results, but they fundamentally show what the algorithm should do.